Killing the Killers: A Leading Indicator of Planetary Ecological Destruction

By, Mark R. Anderson

Founder and Chairman, Orca Relief Citizens’ Alliance

There are two top predators on the planet.

But I am already getting ahead of the story.

On land, animals have no requirement for streamlining, as they would in water, which covers three-quarters of the planet. On land, it is possible to build a house, grow food, make roads, have fingers and toes, store things in buildings, write on paper.

In the ocean, you must do the same things, generally, but all in your head: your house is the sea, with no walls; your map and the roads are solely in your brain. There is no agriculture possible, so all your food comes from mapping, memory, and hunting.

On land, you see. Your brain has evolved visually. Underwater, you see almost nothing, so your brain has evolved to use sonar – the echoes of sound – to see=hear the world, “seeing” it through sound.

Mammals who evolved on land are localized, digital, tribal, visual.

Mammals who were on land but returned to the sea live in an oceanwide environment, digit-free, very social, and acoustic.

If you were a Martian coming to Earth for the first time, you might ask:

a. Who is in charge here? And

b. Over what? And

c. Who is the smartest animal on this planet?

While humans are clearly “in charge” on the planet, it turns out that the story is more complicated than that. Humans are the top predators on land, for example, but orcas (killer whales) are the top predators in the sea. And the sea is three-quarters of the planet’s surface area.

Because humans evolved on land, we can have things like non-streamlined features (our body shape, fingers and hands, toes and feet). This doesn’t mean we are better or smarter; it just means that we are adapted for living on land.

In the water, it’s impossible to have non-streamlined features, so there are no fingers, etc. This also means no pianos, chainsaws, hammers, or any of the tools that require fingers to use.

Imagine that.

Does it mean humans are smarter? No, just dry.

Let’s step back into the Martian’s “shoes” and imagine that this crazy alien wants to understand Earth and its beings solely on their merits.

So, who has the biggest brains on the planet?

Certainly not the land mammals. After all, they have a problem:

While it is clear that biocomputers are the most valuable evolutionary advantage for any animal, the size of land mammals’ brains is dictated by body size; on land, this is relatively small. As John C. Lilly proved long ago, if humans had larger brains, their necks would break under the weight.

For too long, goofy anthropocentric apologist scientists have proposed that, for some unknown reason (putting humans on top), we should express overall animal intelligence as brain weight divided by body weight.

Why?

Does it take a lot of brain to run a body?

No.

In fact, the brontosaurus had two small brains, each the size of a walnut. Wow. Clearly, body weight doesn’t matter.

So, these Martians might want to know: What are the largest brains, the largest biocomputers, the smartest animals, on Earth?

Almost certainly not us.

The Brain Ladder

Why not us? After all, no one else has built modern cities, airplanes, televisions, the Internet, or – video games. Clearly, we are the smartest, right?

Perhaps, but we are land-dwellers. In fact, as in the example above, we came from the oceans, but long ago evolved into terrestrial creatures. By moving from sea to land, we radically changed the evolutionary pressures on our bodies and our brains. Our bodies no longer had to be streamlined, so we could have fingers and long, spindly arms and legs – perfect for manipulating things, but not useful if you want to swim fast in the sea.

We fled predators by going into trees, where that digit manipulation was key to moving around and surviving; we even had tails for a while. Later we moved into caves – another way of avoiding predators. Finally, using our brains (and land), we developed stationary food sources (agriculture) and weapons, neither of which would have been possible in the sea.

Whales are the result of a return of our ancestors to the oceans, where none of these paths were open. No cities, no cave dwellings; predators and prey all in one soup; and no fingers, arms, legs, physical manipulation, or external weapons. Humans have about a 3- to 5-million-year past as a species evolved for land, with all the really exciting stuff that we would consider “civilized” to be in the last 30,000 or so years. Whales, on the other hand, have been in their species for up to 50 million years, evolving all that time for fitness to the sea, often as the top predators.

One benefit of being a sea creature is that you can have a big body. And if our thesis is true – that every mammal has the most brain it can afford – then the oceans allowed for much larger mammalian brains than the land.

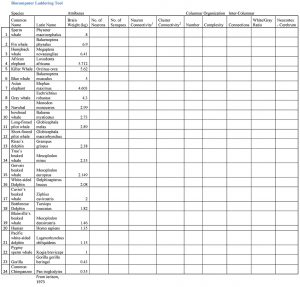

Last year, to understand different biocomputers and their potential power, we worked with two scientists to create version 1.0 (or, more honestly, version 0.9) of the Biocomputer Toolkit – a.k.a., the Brain Ladder.

This is nothing more than a chart of the top 24 biocomputers on the planet, listed first by weight and then with columns for all of the potential structural attributes of mammalian brains that seem to be important in processing data, from a “hardware” perspective. This is really no different from looking at various chip designs or computer architectures and making rough assessments of compute power based on size, number of transistors, smallness of channels, and so on.

The project began by listing all brains by weight (not divided by body weight, which we have clearly rejected), with different columns for different physical attributes that may contribute to computing abilities of one type or another, such as number of neurons, number of synapses, density, columnarization, etc. The project, now in Dr. Benjamin Smarr’s hands, next moves to a scientific crowdsourcing of all of the necessary data to be filled-in in each spreadsheet cell. This will, without doubt, take a number of years.

When complete – or even as we complete any given column – this will act as a toolkit that allows anyone with any point of view regarding the relative importance of these brain attributes to rank the planet’s top brains in one or more informed rankings, or “ladders.”

Here is the toolkit today (click image for larger version):

Why does weight matter? In terms of energy consumption, the brain is the most expensive piece of hardware in the mammalian body; i.e., it consumes the most energy per gram. Just as nature abhors a vacuum, evolution does not tolerate waste. In this case, the cost of each gram of brain weight is an additional requirement of getting more food per day, a process which itself is energetically expensive, and with high survival failure risk.

Translation: Without having to know how every brain works, evolution has provided us with its own assessment. Brains, by weight, are expensive, and evolution only favors expensive tools that increase survival.

Where is the human biocomputer in this first-order ranking? Number 20.

And where are killer whales? Number 5.

The Role and Meaning of Apex Predators

There is no question that humans are the top, or “apex,” predators on the planet; we have better weapons. This is the result of our move onto land.

But 78% of the planet is covered by oceans, and for the last 50 million years the apex predator was the current and past germline of the killer whale (originally, “whale killer”), or Orcinus orca. We just call them orcas.

There is a lot of discussion about the biological importance, role, and meaning of apex predators in an ecosystem, but the short story is simple: apex predators depend upon a food chain which includes species from top to bottom. For this reason, their survival is a good indicator of the health of the whole ecosystem they dominate.

In the case of orcas, they live in all oceans and have varied diets. But there are only two populations of this apex predator that are “resident,” meaning they spend most of their time in one place. They are called the Southern Resident Killer Whale (SRKW) and Northern Resident Killer Whale (NRKW) populations. One resides in the Salish Sea, including Puget Sound, near Seattle; the other is a bit north, in the same waters, off the British Columbia coast.

Why Should We Care?

If we ever find a way to communicate with the brains of this other apex planetary predator, it will likely be through one of these resident populations – both of which have been declared an endangered species by their respective governments.

Is such communication possible? Probably.

Until recently, humans have taken the embarrassingly stupid path of insisting that other animals learn human languages in order to communicate with us – even though we claim to be the smart ones. Dolphins, in captivity, have done well at this, as have chimpanzees, our closest relative on land.

But recently, scientists such as Strategic News Service member Dr. Con Slobodchikoff have found new ways of showing that animals are communicating, and that we can understand them to some extent without their “learning English” or without our even needing to understand their language. More important, he has also shown exactly what, in some cases, they are communicating – again, without needing to understand the language (or system) involved.

This use of pattern recognition via computer has opened the door to expanding our ability to communicate with dogs, cats, and perhaps someday, dolphins and whales. (Orcas are actually large members of the dolphin family.)

The Problem

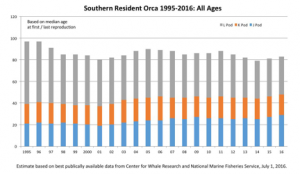

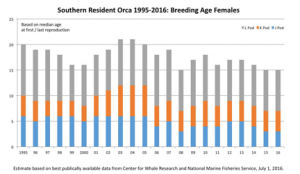

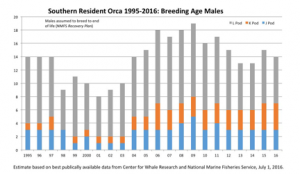

Today, the Southern Resident Killer Whale population is crashing, down to 78 whales from 97 just 20 years ago, and with seven dead in the last year. While calves always die at just under a 50% rate in their first year, almost all of the other deaths have been of prime-age animals – something unseen until the last couple of decades. That timeline, it turns out, perfectly matches the advent and growth of the motorized commercial whale-watch industry.

Orca Relief Citizens Alliance was the first group to predict the population crash, back before it began, in 1997. (In fact, its name was created before the crash – a living reminder that we unfortunately got that call right, before it happened.)

Orca Relief, with money provided by Strategic News Service members, was the first to fund scientific research into the causes of death for the SRKWs, through a study arranged by the University of Washington Friday Harbor Laboratories and conducted by the UW.

That first study, done by Dr. Glenn VanBlaricom and his grad student Carlos Alvarez, was groundbreaking. The authors computer-modeled every single whale and examined every possible cause of death, from salmon count to decadal weather patterns. Their conclusion: shortage of salmon alone did not correlate with whale deaths. But low Chinook salmon count (the vulnerable population of Chinook salmon comprise the main diet of the SRKW) combined with high commercial whale-watch boat count did correlate with orca mortality.

In other words, there was something about motorized whale-watch boats, in bad salmon years, that was killing the whales.

Today, with over 50 international scientific papers on the subject, we know exactly what is killing the killers. We have put it into a single, ordered sentence:

When Chinook count is low, the presence of motorized boats increases the orcas’ need for food, while decreasing their ability to forage, leading to consumption of their own toxin-laden blubber, as they starve to death.

That’s it.

Of course there’s more detail, lots of it. Motorized boat presence leads to a 17% increase in the need for food, as whales swim longer, must take less direct paths to get where they are going, and must dive for longer periods of time, and as their metabolic rates go up from this harassment (whether by intent or sheer ignorance). At the same time, the underwater noise from propeller cavitation sits directly on top of their sonar frequencies. At the currently legal distance of 200 meters, this can reduce orca sonar efficacy by over 95%. They are literally blinded by the boats, and can’t hunt.

An Orca Relief-funded research project by acoustician David Bain found a direct correlation between the number of motorized whale-watch boats and whale mortality rates after the fleet exceeded about 30. Since private boats often flock to the commercial fleet, the fleet itself comprises what the law would call “an attractive nuisance,” doubling the impact on the whales. In other words, 15 commercial motorized craft often easily draws a like or greater number of private motorized boats.

Add in the time and efficiency of harassment during the May-November whale-watch season, using encrypted radio nets and a spotter network that create virtual certainty that whales will be followed by the fleet, from 10am until dusk, and the result is constant harassment and starvation impact.

There is now zero doubt that motorized boat traffic has a severely negative impact on the orcas. Today there are over 50 scientific papers on the negative effects of boats on orcas, most of which are listed on the Orca Relief website.

How dire is the situation? While headcount shows a disaster underway, the news is actually worse. Before there was a whale-watch fleet, the orcas were predated by Sea World and friends, which captured or killed a good number of these animals for display and entertainment purposes. Even so, as soon as the taking stopped, the population rebounded robustly. Since the advent of the fleet, the population has been in a series of declines, and appears unable to rebound.

What’s worse, the damage done by the synergistic negative impacts of boats and low fish count seems to affect the breeding-age whales, those of prime age. Their preferential starvation isn’t just a headcount issue, since their removal reduces the ability of the population to reproduce, to rebound.

Below are three research charts created by Bruce Stedman of Orca Relief, using data from the Center for Whale Research. Keep in mind that we have lost several more whales, mostly from J Pod, since these charts were created.

Clearly, the population is crashing.

Unless a radical change is introduced into this situation, we will soon lose this entire population.

The Solution

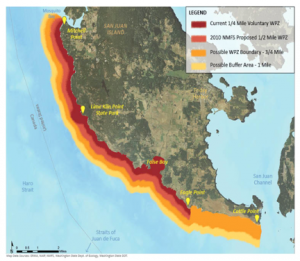

Fortunately, there is a straightforward, science-based solution to this problem: create a small Whale Protection Zone (WPZ) where it is most needed. For the orca, this means the place where the Chinook salmon are most concentrated. Years of records also show that this is the most critical of areas for other behaviors, including feeding and resting.

For the last three years, Orca Relief has been working with a dedicated team of scientists, policy experts, and government officials to create this proposal. In November, it was submitted officially to the National Marine Fisheries Service, where it is currently under review.

The complete proposal can be found here. This is an image of the proposed WPZ:

The rationale behind this proposal is simple: by commercial whale-watch boats being excluded from this small but critical area, the whales will be able to avoid harassment, use their sonar – and thereby not starve – and not have to feed off the toxins in their own blubber.

The rationale behind this proposal is simple: by commercial whale-watch boats being excluded from this small but critical area, the whales will be able to avoid harassment, use their sonar – and thereby not starve – and not have to feed off the toxins in their own blubber.

With a WPZ established, whale-watch operators can remain in business, which will not happen if the whales are driven to extinction. We continue to hope that this group will stop opposing the plan and start supporting it. It’s time to replace short-term greed with long-term greed.

What can you do? Make a donation, and sign the abridged petition of support.

We should all work together to save this amazing and unique population of brilliant resident apex predators.

It’s worth it.

Sincerely,

Mark R. Anderson

Founder and Chairman, Orca Relief Citizens’ Alliance